The most common tick species to bite people and domestic pets use an ambush strategy in order to find a host. Ticks position themselves at the top of a plant stem, or on the edge of leaves, and wait for the host to come close enough for them to mount it.

Ticks pick up a number of signals from an approaching host. The first of these are odours produced by the host’s body. These odours can be picked up by the tick’s unique sensory organ (Haller’s organ) from great distances, and prompt the tick to assume a typical ‘questing’ position (forelegs extended and waving into the air) which allows it pick up wide-ranging signals and to mount the host when it comes close enough. The Haller’s organ is situated on the tarsus (the end segment of the forelegs).

The next signal the tick picks up is carbon dioxide from the host’s breath. Molecules of C02 can also travel some distance.

The final cues to alert the tick that the host is in close enough proximity are vibrations and shadows produced by the movement of the host.

Black-legged ticks (a close relative of the UK wood tick) have been known to pick up human odours from eleven metres away.

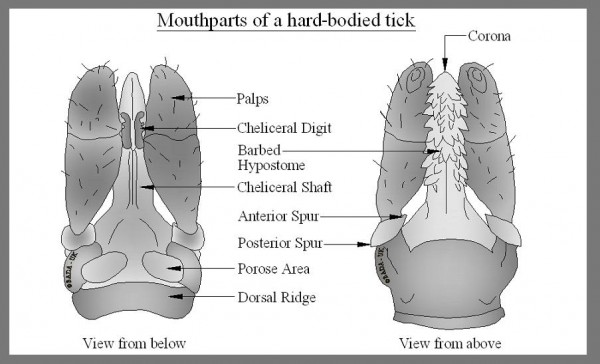

Once a host has been selected, the tick wanders around looking for a suitable feeding site. It then angles its body and, using its sensory palps, guides it chelicerae (cutting limbs) to begin slicing through the layers of flesh. The tick’s hypostome (a barbed feeding tube) and chelicerae are rocked back and forth as the hypostome is inserted into the channel the chelicerae have created. The barbs on the hypostome anchor the mouth parts in place and the tick’s salivary glands secrete a cement (in most hard-tick species) which sets around the mouth parts, fixing them even more securely.

The cutting and rocking motion of the mouth parts, combined with salivary secretions which dissolved tissue, create a pit in the host’s flesh. Salivary secretions also result in the haemorrhaging of blood vessels which form a pool of blood in the pit the tick has created. This pool-feeding process (termed ‘telmophagy’) is in contrast to the feeding process of mosquitoes and other biting insects, which insert their mouth parts directly into a blood vessel (solenophagy).

The more tissue the tick hollows out, the deeper it appears to be embedded. Ticks don’t have a head. Their sensory limbs and mouth parts (termed the ‘Capitulum’) are attached to their main body by the basis capituli (also termed the ‘basal ring’). The Capitulum is sometimes referred to as a ‘false head’ but it is just the mouth parts that become embedded in the skin.

Most argasids are multi-host ticks, feeding repeatedly from minutes to hours, usually at night. Once their feed is complete, they drop off the host. Larvae feed once, while nymphs and adults feed twice or more in order to nourish them through their life stages and, in adults, for sperm and egg production. There is an exception in a few argasids which have non-functional mouth parts.

Ixodids feed once per life stage (larva, nymph and adult), for several days. Some species seek out three hosts for the three life stages (a three-host tick), while others seek two hosts (a two-host tick). In two-host ticks, the first host feeds the larva, which becomes a nymph while on the host, and the second host feeds the adult tick.

Both ixodids and argasids ingest large volumes of blood, several times their body weight. During feeding, saliva is secreted, which serves various purposes depending on the species of tick. Saliva secretion can regulate fluid balance, dissolve the host’s tissue, prevent blood coagulation, anesthetize tissue and, in most ixodids, create cement for secure attachment.

The fluids introduced by the tick to the host can result in a reaction from the body’s immune system.

Tick Feeding Process

The tick uses its palps (limbs with sensory organs) to find a suitable feeding site on the host. It introduces saliva with anaesthetic properties to numb the bite area and begin breaking down the tissue. Special cutting mouth parts (chelicerae) break through and a straw-like mouth part (hypostome) is inserted. The hypostome has back-facing barbs to keep it in place. The tick sucks up blood from ruptured vessels. Saliva flows into the host throughout the feeding process to keep the blood flowing and prevent inflammation.

Localised itching and swelling is common at the site of a tick bite as the body reacts against the tick’s saliva. Severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis have also been described following bites from certain tick species, including the Australian paralysis tick.

Recent research has demonstrated that sensitivities following tick bites may result in long-term allergies. In 2007, the University of Virginia in the USA identified cases of red meat allergy resulting from the bite of the Lone Star tick.

Animals can suffer anaemia, irritation, and allergic reaction, as a direct result of heavy tick infestation. This is termed ‘tick worry’, Ground nesting birds such as grouse, and their chicks, can die from blood loss as well as infection passed on during heavy tick infestations.

It is during the feeding process and the introduction of saliva that transmission of tick-borne diseases occur. The disease-causing organisms are contained in the intestines and salivary glands of the tick and the host becomes infected as the saliva flows into the skin and bloodstream. Incorrect removal of ticks can cause fluids to be squeezed out from the tick into the host, or spilled onto the skin of the host which can also result in infection.

Not all ticks carry tick-borne disease, and not every bite from an infected tick will result in disease transmission. However, sometimes bacteria (such as organisms contained in the soil) can be introduced from the tick’s mouth parts, and this may lead to a bacterial cellulitis (a localised infection of the skin). Scratching at a tick bite, as with any vector bite, can introduce bacteria and result in a skin infection.

The tick’s mouth parts can remain in the skin if incorrectly removed, or scratched off, subsequently resulting in a localised infection. More often than not the body isolates the tick mouth parts and a hard lump will remain. Although it may cause irritation for a while, this usually settles down. Remaining mouth parts can be removed by a doctor or vet if they become troublesome. If there are signs of significant inflammation beyond 48 hours of a tick bite, or signs of infection, it is advisable to seek medical / veterinary advice.

Further details found by clicking on below links:-