Exotic ticks and tick-borne diseases: the need to remain vigilant

Hany M Elsheikha

The Veterinary Nurse, Vol. 4, Iss. 2, 02 Apr 2013, pp 88 – 95

Abstract; Ticks are notorious vectors of numerous infectious (bacterial, protozoal and viral) diseases to animals and humans. Many of the tick-borne diseases (TBDs) can cause significant economic consequences and are challenging to control. Research advances in parasitology and recent changes in the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) have changed views of how exotic tick species and TBDs can be introduced and established in the UK. However, the impact of the PETS tick treatment rule change is still unclear and requires intensive research. In the meantime, veterinary practitioners must remain vigilant and prepared. Public awareness campaigns have already been implemented; however, these need to be expanded to educating the public about the potential risks of exotic TBDs and pre-emptive measures to mitigate these risks. Pet owners’ education and fostering the concept of ‘one health’ are of prime importance. Tick treatment of companion animals entering the UK, although not obligatory, is still necessary to protect travelling and resident pets.

Full article can be accessed at http://www.theveterinarynurse.com/cgi-bin/go.pl/library/abstract.html?uid=97762

Vector vigilance: tick-borne diseases

HANY M ELSHEIKHA discusses the basic biology, ecology, veterinary significance and current treatment strategies relating to ticks, in the first of a two-part article

TICKS are arthropods (phylum Arthropoda) of great medical and veterinary significance.

Ticks are among the most important vectors of pathogens affecting companion animals, livestock and humans (Parola et al, 2005). The increasing number of human and animal cases affected by diseases transmitted by ticks reported in Britain indicates that the interaction between hosts and ticks may be more common than is realised.

A study has revealed that tick infestation prevalence has increased over time at many locations throughout Britain (Scharlemann et al, 2008).

Over the past two decades, climate change seems to have had a marked effect on the number of ticks in the UK and, as a result, the incidence of tickborne diseases (TBDs) is increasing. Additionally, the current emphasis in Europe on sustainable agriculture and extensification is likely to lead to a rise in the tick population and, therefore, an increase in TBD risk.

Ticks have been implicated as a source of disease for more than a century. In 1893, Smith and Kilbourne reported the first description of a tick-borne disease, establishing that the cattle tick transmitted the protozoan Babesia bigemina – Texas cattle fever’s causative pathogen. This remarkable report became the foundation for subsequent work on vertebrate hosts and arthropod vectors.

More information can be found at http://www.vetsonline.com/publications/veterinary-times/archives/n-39-19/vector-vigilance-tick-borne-diseases.html

Antimicrobial Resistance in Leptospira, Brucella, and Other Rarely Investigated Veterinary and Zoonotic Pathogens.

DOGS

Novel Rickettsia Species Infecting Dogs, United States

James M. Wilson, Edward B. Breitschwerdt, Nicholas B. Juhasz, Henry S. Marr, Joao Felipe de Brito Galvão, Carmela L. Pratt, and Barbara A. Qurollo

Molecular prevalence of Bartonella, Babesia, and hemotropic Mycoplasma species in dogs with hemangiosarcoma from across the United States.

Lashnits E, Neupane P, Bradley JM, Richardson T, Thomas R, Linder KE, Breen M, Maggi RG, Breitschwerdt EB.

Bartonella henselae infection in a dog with recalcitrant ineffective erythropoiesis.

First description of Bartonella koehlerae infection in a Spanish dog with infective endocarditis

María-Dolores Tabar, Laura Altet, Ricardo G. Maggi, Jaume Altimira and Xavier Roura

Babesiosis in Essex, UK: monitoring and learning lessons from a novel disease outbreak

Ian Wright

Emergence of Babesia canis in southern England

Maria del Mar Fernández de Marco, Luis M. Hernández-Triana, L. Paul Phipps, Kayleigh Hansford, E. Sian Mitchell, Ben Cull, Clive S. Swainsbury, Anthony R. Fooks, Jolyon M. Medlock and Nicholas Johnson

The UK’s third geographical outbreak of babesiosis in an untravelled dog

https://www.vettimes.co.uk/news/vigilance-urged-after-babesia-confirmed-in-untravelled-dog/

Prevalence and distribution of Borrelia and Babesia species in ticks feeding

on dogs in the U.K.

Abdullah S, Helps C, Tasker S, Newbury H, Wall R

Ticks infesting domestic dogs in the UK: a large-scale surveillance programme

Swaid Abdullah, Chris Helps, Severine Tasker, Hannah Newbury and Richard Wall

http://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-016-1673-4

CANINE VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES – TREATING THIS GROWING THREAT

Canine babesiosis: autochthonous today, endemic tomorrow?

Simon Cook, BSc, BVSc, MRCVS and James W. Swann, MA, VetMB, MRCVS

http://veterinaryrecord.bmj.com/content/178/17/417.extract

Death of Military Working Dogs Due to Bartonella vinsonii Subspecies berkhoffii Genotype III Endocarditis and Myocarditis.

Testing for vector-borne pathogens in dogs:

HANY M ELSHEIKHA identifies emerging concerns associated with CVBD in the UK and provides updates on their diagnosis and management options

THE term canine vector-borne diseases (CVBD) describes a group of diseases in dogs caused by pathogens transmitted by blood-feeding arthropods.

One of the foremost concerns of veterinary authorities in the UK today is the emergence and spread of CVBD, which have become established in many parts of the world, including Europe and the United States.

The increasing risk of vector-transmitted infections constitutes a major threat to canine health worldwide. While the real importance of many of the CVBD is in the veterinary field, they pose a serious risk to humans as well.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to increase awareness of the risk of CVBD all around the world due to the spread of vector ectoparasites (ticks and blood-sucking insects) and – subsequently – the transmitted pathogens.

Until effective preventive strategies against most of the vector-borne pathogens are established, the logical consequence is ectoparasite control.

Equine Borreliosis (Lyme Disease):

Vectors and vector-borne diseases of horses.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23054414

Retrospective Evaluation of Horses Diagnosed with Neuroborreliosis on Postmortem Examination: 16 Cases (2004-2015).

Polysynovitis in a horse due to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection–Case study.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26094517

“LYME DISEASE” IN HORSES

Lyme disease, or borreliosis, is an increasingly suspected clinical condition of horses and other species caused by the tick-borne spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. High rates of seropositivity have been recorded in horses from many regions of the UK and clinical cases certainly occur with the most frequent clinical signs including various combinations of the following: • mild pyrexia • synovial effusions • lethargy • laminitis • weight loss • uveitis • stiffness/Lameness • behavioural changes • muscle soreness • other neurologic problems such as hyperaesthesia or ataxia

CATS

First report of Lyme borreliosis leading to cardiac bradydysrhythmia in two cats

Camilla Tørnqvist-Johnsen, Sara-Ann Dickson, Kerry Rolph, Valentina Palermo, Hannah Hodgkiss-Geere, Paul Gilmore, Danièlle A Gunn-Moore

Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella spp., haemoplasma species and Hepatozoon spp. in ticks infesting cats: a large-scale survey.

Duplan F, Davies S, Filler S, Abdullah S, Keyte S, Newbury H, Helps CR, Wall R, Tasker S

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29558992

Prevalence of ticks and tick-borne pathogens: Babesia and Borrelia species in ticks infesting cats of Great Britain.

Bacterial and protozoal agents of feline vector-borne diseases in domestic and stray cats from southern Portugal

Detection of Leishmania infantum DNA mainly inRhipicephalus sanguineus male ticks removed from dogs living in endemic areas of canine leishmaniosis

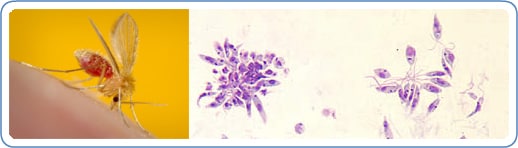

Image: The sand flies that transmit the parasite are only about one third the size of typical mosquitoes or even smaller. On the left, an example of a vector sand fly (Phlebotomus papatasi) is shown; its blood meal is visible in its distended transparent abdomen. On the right, Leishmaniapromastigotes from a culture are shown. The flagellated promastigote stage of the parasite is found in sand flies and in cultures. (Credit:PHIL, DPDx.)

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease that is found in parts of the tropics, subtropics, and southern Europe. It is classified as aNeglected Tropical Disease (NTD). Leishmaniasis is caused by infection with Leishmania parasites, which are spread by the bite of phlebotomine sand flies. There are several different forms of leishmaniasis in people. The most common forms are cutaneous leishmaniasis, which causes skin sores, and visceral leishmaniasis, which affects several internal organs (usually spleen, liver, and bone marrow).

http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3020619/

- Comment

Ticking the wrong boxes

IT IS interesting to see how news of a disease outbreak develops and spreads. In February,Veterinary Record published a short letter from Clive Swainsbury and colleagues at the Forest Veterinary Centre, drawing attention to an outbreak of babesiosis in dogs in Harlow in Essex. Over the previous three months, the disease had been identified in three dogs from three different households. The dogs had been exercised in a local uncultivated park area, andDermacentor species ticks had been recovered from two of them. Significantly, none of the dogs had travelled abroad (VR, February 13, 2016, vol 178, p 172).

Fatal babesiosis in an untravelled British dogVeterinary Record 2006;159:6 179–180

Resolution of spontaneous hemoabdomen secondary to peliosis hepatis following surgery and azithromycin treatment in a Bartonella species infected dog.

Berkowitz ST, Gannon KM, Carberry CA, Cortes Y.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27074964